Robots on the Solar Farm: Practical Jobs Today, Not Hype

The solar industry has reached an inflection point. With over 600 gigawatts of new photovoltaic capacity installed globally in 2024 (IEA PVPS, 2025), utility-scale solar farms now face operational challenges that manual inspection methods cannot economically address. The scale of individual installations has grown dramatically, with the world’s largest solar farm—the Gonghe Talatan Solar Park in China—now exceeding 15 gigawatts of capacity across 609 square kilometres (Solar Tech Online, 2025). The top ten largest facilities globally each exceed one gigawatt and typically span more than 20 square kilometres, creating inspection and maintenance challenges that traditional manual approaches cannot efficiently address.

According to the Raptor Maps 2025 Global Solar Report, equipment-related underperformance has risen 214 percent between 2019 and 2024, resulting in nearly ten billion US dollars in unrealised revenue annually (Raptor Maps, 2025). These losses, equivalent to 5.77 percent of expected output on average, demand a fundamental shift in how operations and maintenance teams approach site monitoring and fault detection.

The economic magnitude of the operations and maintenance challenge extends well beyond annual underperformance losses. With typical O&M costs ranging from six to ten dollars per kilowatt annually across a 20 to 30-year asset lifetime, the cumulative market for solar O&M services represents between 120 and 300 dollars per installed kilowatt over the operational life of a facility. Applied to the current global installed base exceeding two terawatts, this translates to a multi-hundred-billion-dollar market opportunity spanning the coming decades—a market where efficiency improvements of even modest percentages generate substantial value for asset owners and operators.

Robotics represents one solution pathway, but the conversation has been dominated by demonstrations and pilot projects rather than practical deployment guidance. This article examines where solar robotics inspection genuinely adds value in 2025, what drone thermography and robot dog solar farm applications can realistically accomplish, and how these technologies integrate with existing work management systems to deliver measurable operational improvements.

The Established Role of Drones in Utility-Scale PV

Drone thermography for utility PV has moved beyond proof-of-concept trials into routine deployment across mature markets. Thermal imaging cameras mounted on unmanned aerial vehicles can survey hundreds of megawatts in a single day, capturing temperature differentials that indicate module hotspots, bypass diode failures, string-level issues, and inverter anomalies. The economic case for drone-based thermography rests on three foundations: speed, coverage, and safety.

Manual thermography, conducted by technicians walking arrays with handheld thermal cameras, typically covers between ten and twenty megawatts per day depending on site topography and array density. For facilities in the gigawatt scale—now common among the world’s largest installations—manual inspection of the entire site would require weeks or months to complete. A trained drone pilot can inspect the same capacity in a fraction of the time, generating georeferenced thermal imagery that enables precise fault localisation. This speed advantage becomes decisive for large portfolios where periodic inspection cycles must be completed within weather windows or seasonal maintenance schedules.

Coverage presents the second advantage. Ground-based inspection inherently samples the array, with technicians focusing on accessible sections or areas flagged by SCADA underperformance alerts. Drones provide comprehensive surveys that identify anomalies in sections that might otherwise be overlooked until string-level faults propagate to inverter performance metrics. For sites spanning tens or hundreds of square kilometres—as is now typical for facilities exceeding one gigawatt—aerial inspection may be the only practical method for complete site coverage within reasonable timeframes.

Safety considerations have accelerated drone adoption particularly in regions with venomous wildlife, extreme temperatures, or remote sites where emergency response times are measured in hours. Removing technicians from direct exposure to these hazards represents a material risk reduction that operations managers increasingly prioritise alongside cost considerations.

The limitations of drone inspection are equally important to understand. Thermal surveys identify temperature anomalies but cannot diagnose root causes without additional investigation. A hotspot may indicate a cracked cell, a soiled module cluster, shading from vegetation, or an electrical connection issue. The thermal data must feed into a diagnostic workflow that prioritises findings, dispatches appropriate resources, and verifies remediation effectiveness. Furthermore, weather constraints limit deployment. Thermal imaging requires clear conditions with sufficient irradiance to generate meaningful temperature differentials, and aviation regulations restrict operations during high winds, precipitation, or reduced visibility.

Quadruped Robots Enter Solar Operations

Robot dog solar farm deployments represent a more recent development, with commercial prototypes moving from laboratory environments into field trials at operational sites during 2024 and 2025. These quadruped platforms, equipped with optical and thermal sensing payloads, navigate arrays autonomously while conducting patrols that complement or replace certain manual inspection tasks.

The practical advantages of quadruped robots for solar applications centre on persistence, payload integration, and operational flexibility. Unlike drones, which face strict aviation time-of-flight limitations and must return to charging stations, quadruped platforms can conduct extended patrols lasting several hours. This enables inspection protocols that require specific environmental conditions, such as early morning dew patterns that reveal soiling accumulation, or overnight thermal surveys that detect residual heat signatures indicating electrical faults.

Payload integration capabilities distinguish robot dogs from simple autonomous vehicles. Current platforms support mounting brackets for multiple sensor types simultaneously, including high-resolution RGB cameras for visual documentation, thermal cameras for hotspot detection, LIDAR systems for three-dimensional mapping, and environmental sensors for measuring microclimatic conditions across the site. This multi-modal sensing enables robots to gather complementary data streams during a single patrol, correlating visual evidence with thermal signatures and environmental context.

Operational flexibility stems from the ability to deploy robots during conditions unsuitable for drone flight or when human access is restricted. Night-time patrols avoid production interruption and capture thermal data under different irradiance conditions. Inclement weather that grounds drones may still permit robot operation, maintaining inspection continuity during extended weather events. Sites with airspace restrictions, proximity to airports, or regulatory constraints on drone operations can utilise ground-based robots without encountering aviation compliance issues.

The current limitations of quadruped solar inspection platforms must be acknowledged alongside their capabilities. Battery life constrains patrol duration to between three and six hours depending on terrain, payload weight, and navigation complexity. Obstacle navigation, while improving rapidly, still encounters challenges with steep terrain, loose soil, deep puddles, and dense vegetation that may be present at utility-scale sites. Sensor calibration and data quality require careful attention, as vibration from quadruped locomotion can affect image stability and thermal measurement accuracy. Cost per unit remains substantially higher than drone platforms, with lease models emerging to address capital barriers.

The integration of quadruped robots into solar operations is advancing through staged capability development. Early deployments focus on scheduled patrols covering predefined routes, with robots capturing imagery and sensor data for subsequent analysis by operations teams. Emerging capabilities include autonomous anomaly detection, where onboard processing flags potential issues in real time, and dynamic path planning that adjusts patrol routes based on weather conditions or recent fault history. The progression toward fully autonomous inspection, where robots identify faults, prioritise findings, and integrate seamlessly with work management systems, represents the near-term development roadmap.

How Robotics Connect to Work Management and Evidence Documentation

The operational value of solar robotics inspection depends less on the robots themselves than on how inspection data integrates with fault detection, work order generation, and evidence documentation workflows. Isolated thermal images or patrol videos provide limited benefit unless they feed into systems that translate findings into actionable tasks with appropriate prioritisation and resource allocation.

Modern integration approaches link robotic inspection platforms to AI-driven analytics systems that process sensor data, identify anomalies, classify fault types, and generate preliminary diagnostics. When a quadruped robot or drone captures thermal imagery showing a module hotspot, the analytics layer compares the temperature differential against baseline performance data, evaluates the severity based on historical fault progression patterns, and estimates the revenue impact if left unaddressed. This analysis informs whether the finding warrants immediate dispatch of a technician, inclusion in the next scheduled maintenance round, or continued monitoring before intervention.

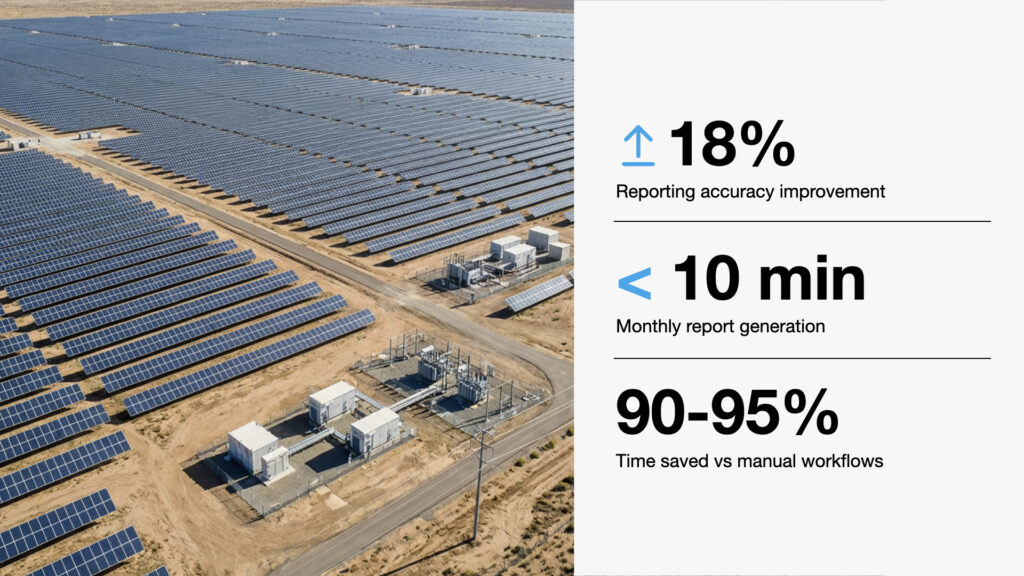

Job card generation represents a critical integration point. Rather than requiring operations staff to manually review inspection reports and create work orders, automated systems can generate detailed job cards that specify fault location using GPS coordinates or array reference identifiers, include relevant thermal and visual imagery, suggest probable root causes based on fault characteristics, and recommend appropriate tools and spare parts for repair crews. This automation substantially reduces the administrative burden on operations teams and accelerates the time from fault detection to corrective action.

Evidence documentation serves both operational and commercial purposes. Detailed imagery captured during robotic inspections provides verifiable records of site conditions before and after maintenance activities, supporting warranty claims, insurance documentation, and performance validation for asset owners. For sites operating under performance guarantees or availability-based contracts, comprehensive inspection records demonstrate due diligence in identifying and addressing issues promptly. The georeferenced nature of robotic inspection data enables precise tracking of fault history at the module or string level, supporting reliability analysis and informing future design decisions.

The workflow integration challenge extends beyond technical data connections to encompass human factors. Operations teams require training on interpreting robotic inspection findings, understanding confidence levels associated with automated fault classification, and making appropriate triage decisions when systems flag potential issues. User interfaces must present inspection data in formats that align with existing operational practices rather than requiring staff to adopt entirely new analytical approaches. Successfully deployed systems balance automation with human oversight, using robotics and AI to handle routine analysis while escalating complex or ambiguous findings to experienced personnel.

Economic Considerations for Australian Solar Sites

The cost-benefit analysis for robotic inspection deployment varies substantially based on site characteristics, existing O&M practices, and regional labour markets. Australian utility-scale solar projects face specific considerations that influence the economics of drone and quadruped robot adoption.

Labour costs represent the dominant factor in Australian O&M economics. The renewable energy sector competes with mining, construction, and other industries for skilled technical personnel, particularly in regional areas where many solar farms are located. The International Renewable Energy Agency reported that while solar PV employed 7.1 million people globally in 2023 (representing 44% of the renewables workforce), labour growth in operations and maintenance has lagged behind installed capacity expansion (IRENA & ILO, 2024). This dynamic creates favourable conditions for automation that can extend the productivity of existing staff or reduce reliance on specialised inspection personnel.

Site scale and geographic distribution influence deployment decisions. Large facilities exceeding one hundred megawatts present clearer economic cases for dedicated robotic inspection capabilities, as the fixed costs of equipment and training amortise across substantial generating capacity. When considering the cumulative O&M expenditure of six to ten dollars per kilowatt annually over a 20 to 30-year operational life, a 100-megawatt facility represents between 120 and 300 million dollars in total O&M spending—creating substantial opportunity for efficiency improvements through automation. Distributed portfolios, where a single operations team manages multiple smaller sites across a region, benefit from mobile inspection solutions that can be transported between locations rather than permanently stationed at individual sites. The tyranny of distance that characterises Australian renewable deployment means that travel time for technician site visits represents a material cost component that robotics can help mitigate.

The in-kind contribution model emerging in Australian deployments provides an alternative to direct capital investment. Solar asset owners provide site access, SCADA data connections, and operations staff time to support technology validation trials, while technology providers supply equipment and technical expertise. This approach, exemplified by arrangements where industry partners commit resources valued at several hundred thousand dollars annually, enables operational testing without requiring upfront capital commitments from either party. Successful trials that demonstrate quantifiable cost reductions or performance improvements then support business cases for permanent deployment or commercial service agreements.

Integration costs deserve careful attention in economic assessments. Connecting robotic inspection platforms to existing SCADA systems, work management software, and documentation repositories requires technical integration work that varies substantially based on system architectures and data standards. Sites with modern digital infrastructure and open APIs face lower integration costs than facilities operating legacy systems. The cumulative cost of SCADA integration, analytics platform development, staff training, and ongoing system maintenance may exceed the direct hardware costs for robotic platforms, particularly during early deployments where reusable templates and standardised procedures have not yet been established.

Regulatory compliance represents an additional cost consideration specific to drone operations. The Civil Aviation Safety Authority requires commercial drone pilots to hold remote pilot licences (RePL) and operations to comply with regulations covering airspace restrictions, flight planning, and safety management (Civil Aviation Safety Authority, 2025). Sites near controlled airspace or in areas with competing aviation activity may face limitations on drone deployment windows. Quadruped robots, operating as ground vehicles rather than aircraft, avoid aviation regulations but must still comply with workplace health and safety requirements governing autonomous equipment operation near personnel.

The emerging service model, where technology providers offer inspection services on a per-megawatt or per-patrol basis rather than selling equipment, addresses some economic barriers. This approach converts capital expenditure to operating expenditure, reduces the need for in-house technical expertise on robotic platforms, and allows operations teams to scale inspection frequency based on seasonal needs or performance trends. Service models require careful specification of deliverables, response times, and data formats to ensure alignment with operational requirements.

The Path to Autonomous Solar Operations

The current state of solar robotics inspection represents an intermediate stage in a longer trajectory toward autonomous operations. Understanding this progression provides context for evaluating technology investments and partnership opportunities.

The autonomy framework adapted from automotive industry classifications describes five levels of automation applied to solar farm operations. Level zero denotes manual operations where all monitoring, inspection, and maintenance are conducted by human personnel supported only by basic SCADA systems. Level one introduces assisted operation through tools that gather and display data but rely on human interpretation and decision-making. Level two achieves partial automation where AI systems detect patterns, generate reports, and classify issues, with humans reviewing findings and approving actions. Level three enables conditional automation with AI systems executing diagnostics and recommending or dispatching actions under known conditions, requiring human management only for exceptional cases. Level four represents high automation where integrated AI and robotics conduct routine inspections and planned maintenance, with human input necessary only for complex issues or regulatory requirements. Level five describes full automation with end-to-end autonomous plant operation including adaptive strategies and corrective maintenance under minimal human oversight.

Current robotic inspection deployments primarily operate at level two and early level three. Robots execute predefined patrol routes and capture sensor data autonomously, while AI systems process findings to identify potential faults and generate preliminary job cards. Human operators review these findings, validate classifications, prioritise actions, and dispatch maintenance resources. The human remains firmly in the supervisory role, with automation handling routine data collection and analysis but deferring to human judgment for operational decisions.

The progression to level four automation, where robots conduct inspections and maintenance tasks with minimal human supervision beyond exception handling, requires advances across multiple technical domains. Enhanced sensor fusion must reliably distinguish between fault conditions and benign variations in operational parameters. Improved navigation capabilities must handle unstructured environments including vegetation encroachment, weather-related obstacles, and temporary site modifications. Manipulation capabilities enabling robots to perform simple maintenance tasks such as module cleaning, connector verification, or vegetation trimming must achieve reliability levels acceptable for unsupervised operation. Integration frameworks must coordinate multiple robotic platforms, prioritise tasks based on production impact, and manage charging logistics to maintain continuous operational coverage.

The Australian context presents both opportunities and challenges for advancing solar automation. The country’s high solar resource quality and aggressive renewable energy targets create strong economic drivers for innovations that reduce LCOE and improve grid integration. The skilled labour shortage provides compelling business cases for automation that extends workforce productivity. However, the relatively small domestic market compared to deployments in the United States, Europe, or Asia means that Australian-developed technologies must target international commercialisation to achieve scale. This reality shapes technology development priorities toward solutions with global applicability rather than addressing uniquely Australian challenges.

Research collaborations between universities, industry partners, and government agencies through programmes like the Australian Renewable Energy Agency’s funding initiatives accelerate technology development by sharing risks and costs across multiple stakeholders. These partnerships enable field validation at operational sites that would be prohibitively expensive for early-stage companies or research groups to access independently, while providing asset owners with early exposure to emerging technologies and influence over development priorities.

The timeline for widespread deployment of highly autonomous solar operations remains uncertain and will vary across markets based on labour costs, regulatory environments, and asset owner risk tolerance. Conservative projections suggest that level four capabilities may see initial commercial deployment in the latter half of the 2020s, with broader adoption occurring through the 2030s as costs decline, capabilities mature, and operational track records demonstrate reliability. The pathway depends not only on technological progress but also on developing workforce capabilities to supervise autonomous systems, establishing regulatory frameworks that appropriately manage novel risks, and building investor confidence in automated operations through demonstrated performance data.

Frequently Asked Questions About Solar Robotics Inspection

What can a robot dog actually do on a solar farm?

Quadruped robots currently excel at scheduled patrol routes where they capture visual and thermal imagery of module arrays, inverters, and site infrastructure. The robots navigate autonomously along predefined paths, continuously documenting site conditions through multiple sensor types. Advanced deployments incorporate real-time anomaly detection where onboard processors flag potential issues for subsequent review. Robots also conduct environmental monitoring, capturing data on vegetation growth, wildlife presence, and weather conditions that affect operations. The key limitation is that current platforms primarily serve inspection and documentation roles rather than performing physical maintenance tasks, though manipulation capabilities for simple tasks like connector verification are under development.

Are drones still needed if you have AI analytics?

Yes, because AI analytics and drone inspection serve complementary rather than redundant functions. AI systems analyse data streams from SCADA systems, weather stations, and inverter controllers to identify performance anomalies and probable fault locations. Drones then provide the visual and thermal confirmation necessary to validate these findings and characterise fault severity. AI might detect that a specific inverter shows reduced output, but drone thermal imaging reveals whether this stems from a single failed module, string-level issues affecting multiple modules, or inverter component problems. The combination of AI-driven fault detection and drone-based visual verification substantially reduces the time and cost of diagnosing issues compared to either approach used independently. Furthermore, comprehensive periodic drone surveys can identify developing issues that have not yet manifested in SCADA performance data, enabling proactive intervention before faults impact production.

How do robots link to job cards and evidence packs?

Integration occurs through analytics platforms that process robotic inspection data and connect to work management systems. When a robot captures imagery showing a potential fault, the analytics system processes the visual or thermal data to classify the issue type, assess severity, and determine the probable location within the array. This analysis generates a structured data record containing GPS coordinates, fault classification, supporting imagery, and estimated production impact. The platform then automatically creates a job card in the work management system populated with this information, assigns priority based on fault severity and revenue impact, and attaches the original imagery and sensor data as an evidence pack. Technicians receive job cards on mobile devices showing precise fault locations, visual references for what they should expect to find, and recommended repair procedures based on fault type. After completing repairs, technicians can upload verification images through the same system, creating a complete documentation trail from initial detection through remediation confirmation.

What are the cost considerations for Australian sites?

Australian deployments must account for several cost factors beyond equipment pricing. Robotic platform costs typically range from forty thousand to one hundred and twenty thousand Australian dollars for quadruped systems depending on sensor payloads and autonomy capabilities, while commercial-grade inspection drones cost between fifteen thousand and sixty thousand dollars for turnkey systems including thermal cameras. However, integration costs for connecting platforms to site SCADA systems and work management software often equal or exceed hardware costs for initial deployments. Labour costs for training operations staff, developing standard operating procedures, and managing regulatory compliance add further expense. The distributed nature of Australian solar deployment means that mobile inspection services, where providers transport equipment between sites, may offer better economics than dedicated platforms for portfolios with multiple smaller facilities. Emerging service models charging between three and ten dollars per megawatt for robotic inspections present alternatives to capital investment, converting expenses to operating costs and avoiding the need to build in-house robotics expertise.

Separating Reality from Roadmap in Solar Robotics

The application of robotics to solar farm operations has moved decisively beyond demonstration projects into practical deployment. Drones conducting thermal surveys have become standard practice at well-managed utility-scale sites, while quadruped inspection robots have entered field trials that will determine their commercial viability. The value these technologies deliver stems not from futuristic capabilities but from practical improvements in inspection speed, coverage, and safety combined with integration into work management systems that translate findings into action.

The economic case for robotic inspection depends heavily on site-specific factors including scale, labour costs, and existing operational practices. Australian solar operators evaluating these technologies should focus on demonstrated capabilities rather than aspirational roadmaps, insist on quantifiable performance metrics from pilot deployments, and carefully assess integration costs alongside equipment pricing.

The progression toward highly autonomous solar operations will unfold incrementally over years rather than emerging suddenly from breakthrough innovations. Current robotic capabilities represent important steps along this pathway, delivering measurable value today while establishing the operational frameworks and data infrastructure that will enable more sophisticated automation in future. Operators who engage thoughtfully with these technologies now, establishing partnerships that allow practical evaluation under real site conditions, position themselves to benefit from capabilities as they mature while avoiding the risks of premature commitment to unproven approaches.

For solar asset owners and operations teams considering robotic inspection deployment, the critical questions concern integration rather than technology specifications. How will inspection data flow into existing work management systems? What training will operations staff require to interpret findings and manage robotic systems? How will costs and benefits be measured to support continued investment decisions? Addressing these operational questions determines whether robotics deliver lasting value or become expensive tools that gather data without improving outcomes.

Partner with P2AgentX to explore practical robotics integration for your solar portfolio. Our approach combines AI-driven analytics with emerging robotic capabilities, focusing on measurable operational improvements rather than technology demonstration. Contact us to discuss how integrated automation can address the specific challenges your sites face.

P2AgentX develops AI and robotics solutions for autonomous solar farm operations, with deployments at utility-scale sites across Australia. Our P2Chat platform and P2Dingo robotics system integrate inspection data with work management workflows to reduce O&M costs and improve fault response times.

References

Civil Aviation Safety Authority. (2025). Drones. Australian Government. https://www.casa.gov.au/drones

International Energy Agency. (2025). Global energy review 2025. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025

International Energy Agency Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme. (2025). Snapshot 2025: Global PV market trends. IEA PVPS. https://iea-pvps.org/snapshot-reports/snapshot-2025/

International Renewable Energy Agency, & International Labour Organization. (2024). Renewable energy and jobs: Annual review 2024. https://www.irena.org/Publications/2024/Oct/Renewable-energy-and-jobs-Annual-review-2024

Raptor Maps. (2025). 2025 global solar report. https://raptormaps.com/resources/2025-global-solar-report

Solar Tech Online. (2025, September 11). World’s largest solar farms 2025: Complete guide to mega projects. https://solartechonline.com/blog/largest-solar-farms-world-2025/